As some of you might know, I'm currently working at an internship at the Rare Books and Manuscripts Division of the Indiana State Library. Going into the internship, I had more or less no idea what I would be doing for the duration. During my initial interview it sounded like I would be digitizing documents and photos for the majority of my time, which I was OK with, as I never expect work to be particularly exciting.

Fortunately, there turned out to be a lot more to the position than scanning and data entry. My primary responsibility has been the processing and cataloging of collections donated to the Library by individuals. My first collection consisted of thousands of news clippings on the White River Park State Games, so if you're looking for an expert on an amateur sports competition that went defunct in the early 90s, I'm your guy.

My second collection however, titled the John M. Smith Collection after its creator/donater, was incredibly fascinating. Mr. Smith is (Was? I'm unclear on his current state. He was alive in 2011 when the collection was donated) an attorney from Auburn, Indiana who I presume got his undergraduate degree in history and remained interested in the study. His collection of historical documents and artifacts was close to 1000 items, most of them from the late 19th and early 20th century, largely collected during the 1960s throughout the 1980s. Judging by some of the marked prices and invoices included in the collection, I'd say its total worth approaches $10,000.

I've taken photos of some of the more interesting pieces and provided a little light interpretation.

This is a land warrant issued to George Rogers Clark, arguably Indiana's most notable military hero. Clark was to be awarded a cash bounty for the recruitment of his battalion during the Revolution, but forewent the cash and took 550 acres of land in its stead. Keep in mind that at this point Virginia still included West Virginia and Kentucky, which were largely unsettled by white people, so the government had a great deal of land to distribute. This wasn't the only treasury warrant issued to Clark, though I don't know what the final total value of his award was.

As an artifact, the warrant is in excellent condition. The wax seal's survival is particularly unusual.

This is a reproduction of The Chippewanuck Medal. The Medal was discovered in 1872 near the banks of Chippewanuck Creek in Newcastle Township. On the front is King George III and on the reverse is the Royal Crest of England, old enough to still contain the lilies that represented the Crown's claim on the Kingdom of France, which it relinquished in 1801.

During colonization, many of these medals were created to be given to Indian chiefs at the conclusion of treaty negotiations. This one was more than likely awarded to a Chippewa Chief in Indiana between 1786 and 1796, and was then taken by a Potawatomi warrior after the conclusion of a furious battle over prime hunting grounds. When the Potawatomi were forced to leave the state, the medal was left behind, likely buried with its most recent owner.

In the early 20th century one of the most popular souvenirs for tourists were ready-made photo albums, likely because very few people had the ability to easily take high quality pictures themselves as cameras and their related equipment were still very expensive and cumbersome. The Smith collection contained dozens of these albums from Indianapolis, Fort Wayne, Terre Haute, French Lick, Bloomington and New Harmony. The changes over time are most evident in the Indianapolis photos. This 1878 photo is of the Circle in downtown Indianapolis, taken facing north. You can see the steeple of Christs' Church Cathedral at the center of the photograph. At this time, the "Governor's Circle," home of the Governor's Mansion until 1857, was a public commons. The Soldier's and Sailor's Monument would not be constructed until 1888.

This is a map of Indiana in 1840, easily the oldest map of the state I've seen in person and nearly as old as a map of Indiana State (est. 1816), as opposed to Indiana Territory, can get. The division of counties is very nearly the same as it is today, save for the fact that at this point Indiana still contained an Indian reservation for the Miami and Delaware tribes in what is now Howard, Tipton and eastern Clinton Counties. Shortly after this map was created the last of Indiana's recognized tribes would be forced to move west, freeing this land for white settlement and allowing the last two Indiana counties to be formed in 1844. Initially Howard County was named Richardville County, in honor of Jean Baptiste Richardville, last civil chief of the Miami Indians. Unfortunately, even this small gesture would be done away with just 2 years later, when the county was given the name it holds today in honor of Rep. Tilghman Howard.

You might also be able to make out the word POTAWATAMIE written across several counties in the northwestern part of the state. This was after the tribe had been official removed from the state and sent to Kansas via the Potawatmie Trail of Death, but some members of the tribe remained behind, fugitives from the law. The label on the map is intended to be a warning for travellers through the area.

A few other interesting bits about this map: you can see the importance of the Wabash Valley in this map very clearly. Indianapolis had only been around for 20 years at this point, and while it was a significant city, it was not the transportation hub it is today (Partially because the city founders drastically overestimated the depth of the White River). Instead, in these days before railroads were ubiquitous, the state and country still heavily depended on canals to move people and freight. This made the Wabash River, with its canal connection to the Great Lakes, the main artery of Indiana and contributed greatly to the growth of many of the cities along this route (this is where the "port" in Logansport originates).

Unfortunately, I can't provide a lot of background about this item. It is a "recipe" book from the 1880s from the Benton, Indiana area. However, it isn't a cookbook, but instead is full of medicinal recipes for the treatment of illness in humans and animals. The book was clearly carried around by its original owner for a great deal of time, almost twenty years, and evidently contains the sum of his knowledge when it comes to slaves and liniments. I find this idea, that this book was a closely held personal object to someone for years and years, even more fascinating than the contents themselves.

Transcription of left page: To make Pettit's Eye Salve

Take any quantity of white precipitate mix with three times as much hog's lard.

For inflammation, sore eyes, apply a poultice of scraped turnip.

Sure Cure for Acne:Bore the heart out of Ironwood and put it in rie [sic] whiskey.

I was surprised by this item, as it's a bit out of place with the rest of the collection. In this picture you can see a large wallet, it's accompanying pocket dictionary and a number of furlough and pass documents for WWI veteran Robert P. Hodge. The wallet was included in the collection just as it was last used in 1918, complete with train ticket stubs, personal notes, receipts and these passes.

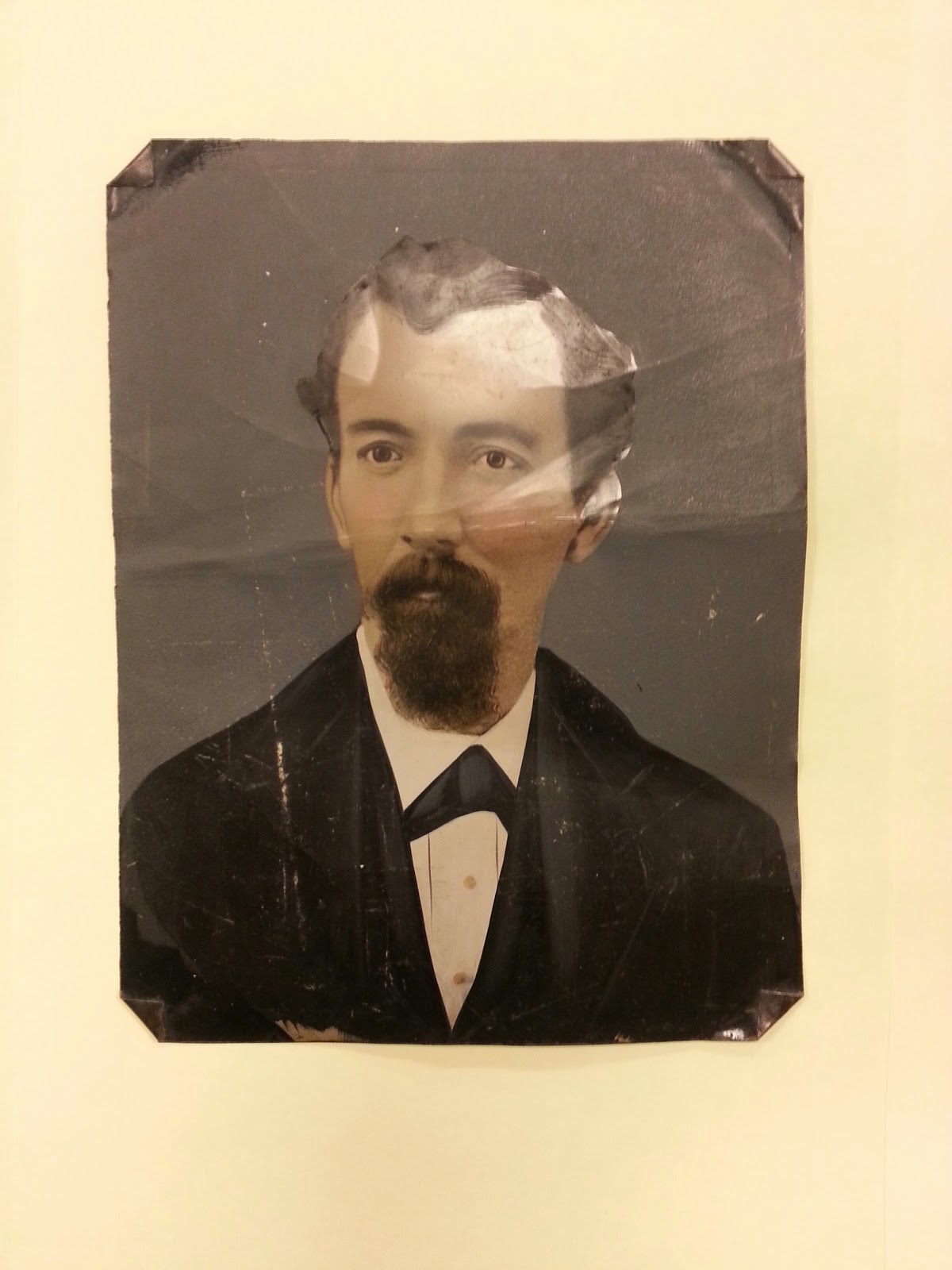

Here's another one I don't have much (any) information on, but is interesting for the type of item. Tintypes (Actually made of iron, not tin) were one of the earliest methods of photography, coming after the daguerrrotype and ambrotype. One of the primary advantages of the tintype was that it could be captured, developed and given to the customer in a much shorter period of time than previous techniques. While this one has some significant damage, it is in unusually good condition for the medium.